Keywords used strategically: Peekskill USA, Peekskill riots, Paul Robeson concert, 1949 riots, civil rights, McCarthyism, labor unions, Peekskill riot PDF, Peekskill 1949, anti-communist protests, Cold War America

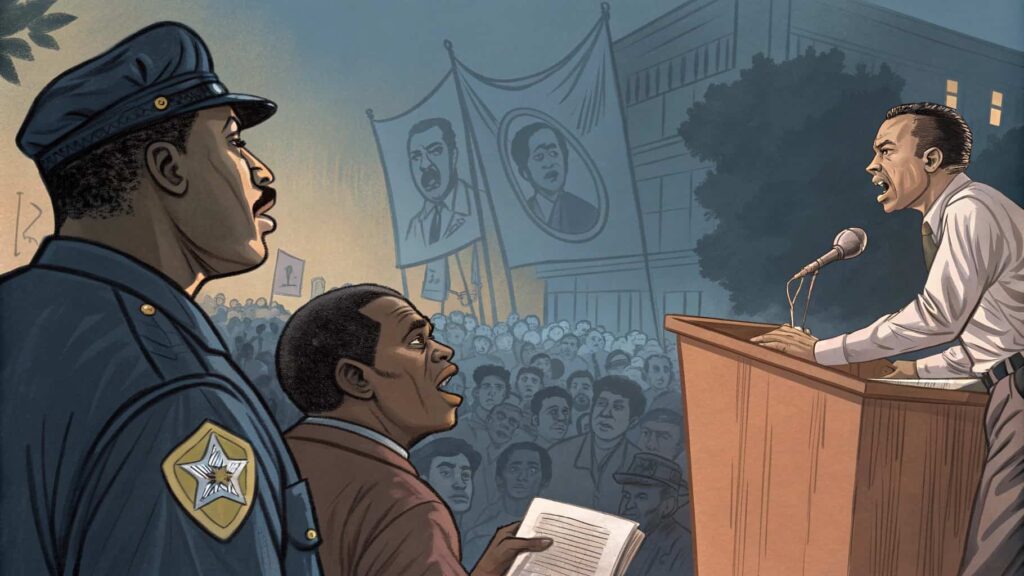

In the summer of 1949, a quiet town in New York became the epicenter of national outrage and violent unrest. The Peekskill riots—fueled by racism, anti-communist hysteria, and Cold War paranoia—forever changed the way the nation viewed free speech, civil rights, and political dissent.

Peekskill USA, also the title of Howard Fast’s vivid eyewitness book, documents how a peaceful concert honoring civil rights leader and singer Paul Robeson was attacked by hate-fueled mobs. This event is more than a historical footnote—it is a powerful lesson about the dangers of political extremism, mob mentality, and institutional silence.

Who Was Paul Robeson – And Why Was He Targeted?

Before understanding the riots, it’s crucial to understand Paul Robeson. He was more than a baritone singer and actor—he was a civil rights activist, union supporter, and outspoken critic of racism and U.S. foreign policy.

In 1949, Robeson gave a speech at the Paris Peace Conference, allegedly saying that African Americans should not support the U.S. in a war against the Soviet Union—a statement widely misquoted and weaponized in American media.

As McCarthyism rose, Robeson was labeled a “communist sympathizer”, even though his main advocacy was for racial equality and workers’ rights. This made him a target for right-wing groups and veterans’ organizations.

Setting the Stage: Peekskill, NY in 1949

Peekskill, a small, working-class town north of New York City, had a large population of World War II veterans and conservative citizens. When Robeson announced a concert there on August 27, 1949, organized by the Civil Rights Congress, right-wing groups and veterans’ associations reacted with fury.

Flyers circulated branding Robeson a “Red”, and demands grew to cancel the concert. When organizers refused, a large and violent protest was all but inevitable.

The First Riot – August 27, 1949

An Ambush of Hatred

As concert-goers began to gather, mobs surrounded the area, shouting racial slurs, carrying anti-communist signs, and waving American flags. When the concert was abruptly canceled due to security fears, the mobs attacked attendees as they left.

Dozens were injured. Cars were smashed. Robeson never even made it to the venue that day.

Despite the brutal attacks, no arrests were made. The police, though present, largely stood by.

A Resilient Comeback: The Second Concert on September 4

15,000 Stand Against Hate

Determined not to be silenced, Robeson and the organizers rescheduled the concert for September 4, 1949, this time with significant security support from labor unions. Workers from steel mills, dockyards, and shipyards formed human chains to protect the event.

The concert took place successfully with Paul Robeson, Pete Seeger, and other artists performing to a crowd of nearly 15,000.

Violence Returns After the Music Ends

As people left, mobs attacked again. Rocks, bottles, and even makeshift explosives were hurled at cars and buses filled with families and children. Over 140 people were injured, including Eugene Bullard, the first Black American fighter pilot, who was beaten by both civilians and police.

Yet again, no one was held accountable.

Also read: Samocillin

Media and Government Response: Silence and Complicity

Instead of condemning the violence, local and national media blamed Robeson and his supporters. The narrative shifted from victimhood to guilt by association with communism.

Governor Thomas Dewey, despite being asked to intervene, claimed the attacks were the fault of Robeson’s supporters for “inciting violence.”

A grand jury later ruled that the riots were not motivated by racism or antisemitism—but by “Americanism.” The perpetrators were never punished.

Impact on Civil Rights, Free Speech, and Cold War America

The Peekskill riots highlighted the dangerous intersection of racism, anti-Semitism, political paranoia, and state negligence.

- Free speech was suppressed.

- Civil rights supporters were beaten.

- Labor unions became defenders of civil liberties.

For Robeson, the incident was a turning point. His passport was revoked, and his career was slowly suffocated by blacklisting. But his legacy—and that of Peekskill USA—lived on.

Howard Fast’s “Peekskill USA” – A Witness in Words

One of the most vivid accounts of the event is Howard Fast’s 1951 book Peekskill USA, which was banned in many libraries during the McCarthy era. The book includes:

- Eyewitness accounts

- Speeches from the concert

- Details of police inaction

- The cultural fallout

Today, many search for a “Peekskill USA riots free PDF” to learn what really happened. You can still find versions online through civil rights archives and open libraries.

Peekskill Riots and Music: Protest Through Song

Music became a form of resistance. Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie composed songs about Peekskill, capturing the fear, bravery, and solidarity.

Notable protest songs include:

- “Hold the Line” – Pete Seeger

- “The Peekskill Story” – The Weavers

- “My Thirty Thousand” – Woody Guthrie

Also read: 5starsstocks.com dividend stocks

Long-Term Legacy of the Peekskill USA Riots

1. Civil Rights Movement Inspiration

The bravery shown by Robeson and the concertgoers inspired future generations of activists. The Peekskill concert was a precursor to Selma, Montgomery, and the March on Washington.

2. Unions as Protectors of Rights

Peekskill was one of the rare moments in U.S. history when organized labor protected free speech with physical courage. It redefined the role of unions beyond wages—toward social justice.

3. A Lesson in Mob Mentality

Peekskill revealed how fear-mongering and propaganda can lead to mob violence. The attackers weren’t only extremists—they were everyday people, radicalized by media and fear.

Peekskill Today: Healing and Remembering

Decades later, the town of Peekskill has changed. In 1999, the 50th anniversary of the riots, a public ceremony of reconciliation was held. Paul Robeson Jr., Pete Seeger, and others gathered to honor the victims.

Peekskill’s diverse and progressive community now works to ensure that history is not forgotten.

FAQs About the Peekskill Riots of 1949

Q1: What were the Peekskill riots?

The Peekskill riots were two violent attacks on peaceful concertgoers in 1949, organized around a Paul Robeson concert. The attacks were fueled by racism, anti-communism, and political paranoia.

Q2: Why was Paul Robeson targeted?

Robeson was an outspoken civil rights activist and perceived communist sympathizer. His progressive views clashed with Cold War conservatism and racism.

Q3: Was anyone arrested after the riots?

No. Despite over 150 injuries, no one was held legally responsible for the violence.

Q4: What role did labor unions play?

Labor unions protected concertgoers during the second concert, forming human chains and organizing defensive lines.

Q5: Where can I read “Peekskill USA” for free?

Search “Peekskill USA Howard Fast free PDF” on archive websites like Internet Archive or ZLibrary for accessible versions.

Q6: Did these riots affect Robeson’s career?

Yes. Robeson faced blacklisting, passport revocation, and limited opportunities after the event.

Q7: What songs were inspired by the Peekskill riots?

Songs by Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, and The Weavers were directly inspired by the events, documenting the resistance in music.

Q8: How many people attended the second concert?

Approximately 15,000–20,000 people attended the second concert on September 4, 1949.

Q9: What was the government’s response?

Local and state officials largely blamed the victims, refused protection, and dismissed lawsuits.

Q10: Why is Peekskill USA still relevant today?

It serves as a warning about the dangers of unchecked bigotry, propaganda, and suppression of free speech.

Conclusion: Why Peekskill USA Must Not Be Forgotten

The Peekskill riots of 1949 are a reminder of how quickly democracy can falter when hatred is normalized, and truth is silenced. From Robeson’s courage to the unionists’ solidarity, it is a story of resistance—and resilience.

As more people search for the Peekskill USA riots PDF, we must continue telling the story, so that the pain of the past becomes a lesson—not a blueprint—for the future.

Related post